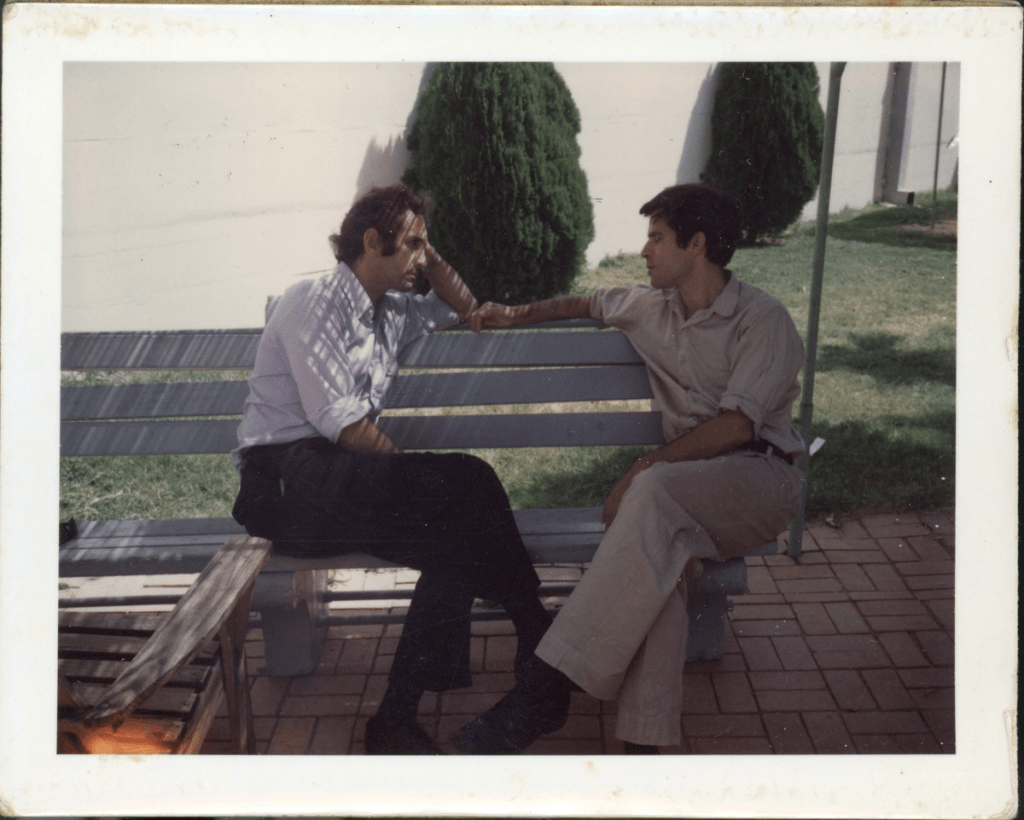

I met Randy Kehler a couple of times, but knew him mostly by his public actions and reputation. The picture above is from my last entry in PoliticsOutdoors, posted a little more than a year ago, a comment on Daniel Ellsberg’s death.

The picture features Randy on the right and Daniel Ellsberg on the left. Ellsberg said that he never would have released the Pentagon Papers had he not learned of Kehler’s commitment and his sacrifice. Kehler had returned his draft card during the Vietnam War, eschewed conscientious objector status, and spent nearly two years in federal prison for his acts of conscience.

Randy died last month at the age of 80, of chronic fatigue syndrome.

There’s no small irony here, as Randy Kehler was a tireless organizer for peace and democracy. He came up with the idea of putting the nuclear freeze proposal on the ballot in a few Western Massachusetts Congressional districts for the 1980 presidential election. The freeze passed by large margins, even as the districts went for Ronald Reagan, part of a Republican landslide.

But the referenda demonstrated the nuclear freeze proposal’s strong appeal. The wins pointed progressives to a viable issue and a workable strategy. Every place the freeze appeared on a ballot over the next several years, it won decisively, and a national movement took off, with Randy Kehler among the key leaders. He served as the first national coordinator of the freeze campaign and testified before Congress.

And, though Reagan–the movement’s prime target–was reelected in another landslide in 1984, it was a different Reagan, one who acknowledged the horrors of nuclear war and offered arms control proposals to the Soviet Union to try to take the steam out of the movement. When a new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev accepted America’s grossly asymmetrical proposals–offers intended to be rejected–Reagan said yes. Agreements on Intermediate range nuclear missiles in Europe (INF), and then strategic weapons (START), gave reformers in the East space to work, leading to the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Today, the global total of nuclear warheads is about less than 1/5 of what it was in the 1980s. That’s still plenty, but it could have been much worse. (Ulp, it could still be.)

Randy Kehler was a great strategist, but his actions weren’t all strategic. He and his wife, Betsy Corner, lost their house to the federal government because they refused to pay taxes supporting preparations for war. The story is told in Clay Risen’s good obituary in the New York Times, in another obit by Diane Broncaccio in one of Kehler’s local papers, the Amherst Bulletin, and in a documentary, An Act of Conscience. The local papers quote Kehler’s neighbors who testify to his engagement and his kindness.

I’m reminded that Henry Thoreau, who got more mileage out of war tax resistance with far less sacrifice, announced that he would always pay local taxes because he wanted to be a good neighbor.

Randy Kehler’s life was consequential in ways that he could not have anticipated, and even after his passing, it remains a model.

Clay Risen picked exactly the right Kehler quote as an epitaph:

“Don’t ever, ever assume that anything you do, particularly if it’s an act of conscience, won’t make a difference.”

Thanks for this, David. Hope all is well with you and your family. da

Dale! What a treat to see your name across the screen. Hope all is well.

Pingback: Why the blanket J6 pardons are even worse than you thought | Politics Outdoors