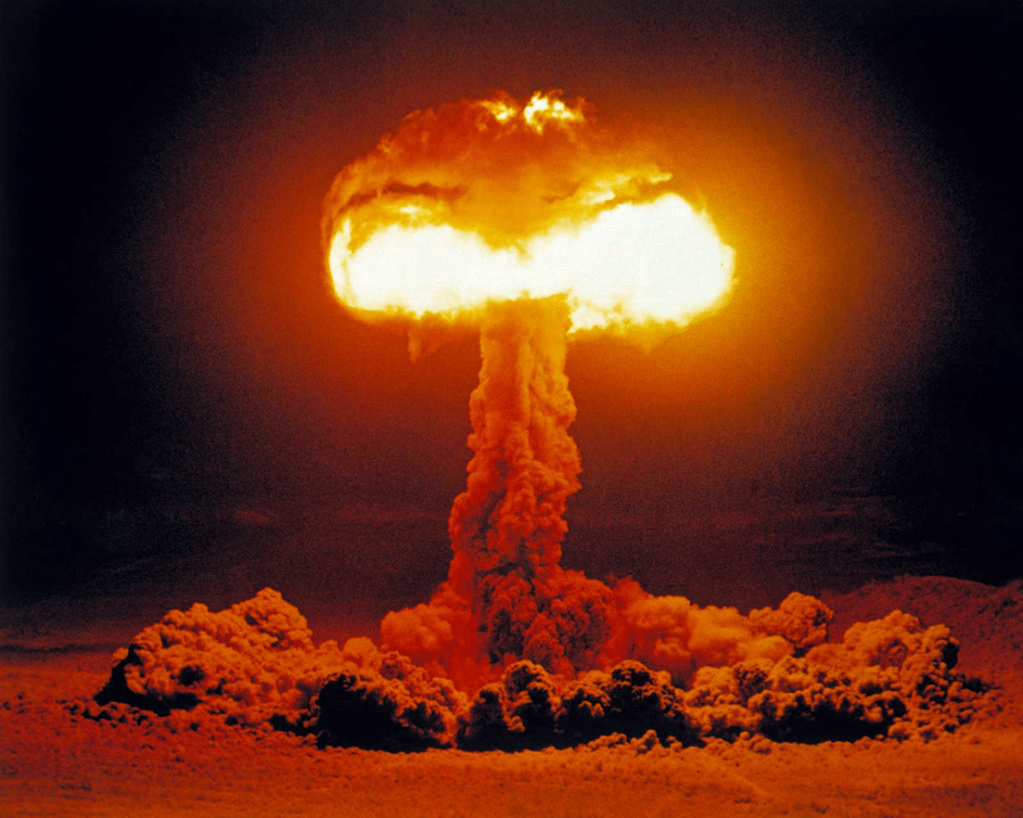

Donald Trump announced that the United States would start testing its nuclear arsenal again–after foregoing nuclear weapons testing since 1992, when the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union fell apart. In doing so, he effectively announced a political challenge to peace activists around the world.

There are many reasons to be concerned about the increased costs and dangers of a new era in nuclear weapons politics, but it’s always hard to get people to pay attention. Since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, activists have campaigned on the existential horrors nuclear weapons represent, demanding restraint–or even disarmament. But most of us are very distant from the development and deployment of nuclear weaponry. We’ve seen nuclear weapons and war in books, but not in real life. Think of the contrast with all the other things that animate social protest movements. And antinuclear campaigners have a hard time convincing audiences of less scary alternatives in a scary world.

There is a pattern of protest and policy that’s played out since 1945: someone notices an identifiable threat from the arms race and points to it to lodge larger criticisms. Over the years, these visible threats have included: the dangers of nuclear testing, including radioactive fallout; development of a new and expensive weapons system (the B-1 Bomber or the MX missile); cavalier rhetoric about nuclear war suggesting incompetence in the White House; or conspicuously ineffective civil defense drills to protect populations.

Sometimes these campaigns are boosted by books, movies, or tv shows illustrating the danger. Think of Dr. Strangelove, Failsafe, or The Day After. Some of the movies don’t stand up so well as movies, but recent films have been much better: Oppenheimer and A House of Dynamite are suitably horrifying and worth seeing as movies.

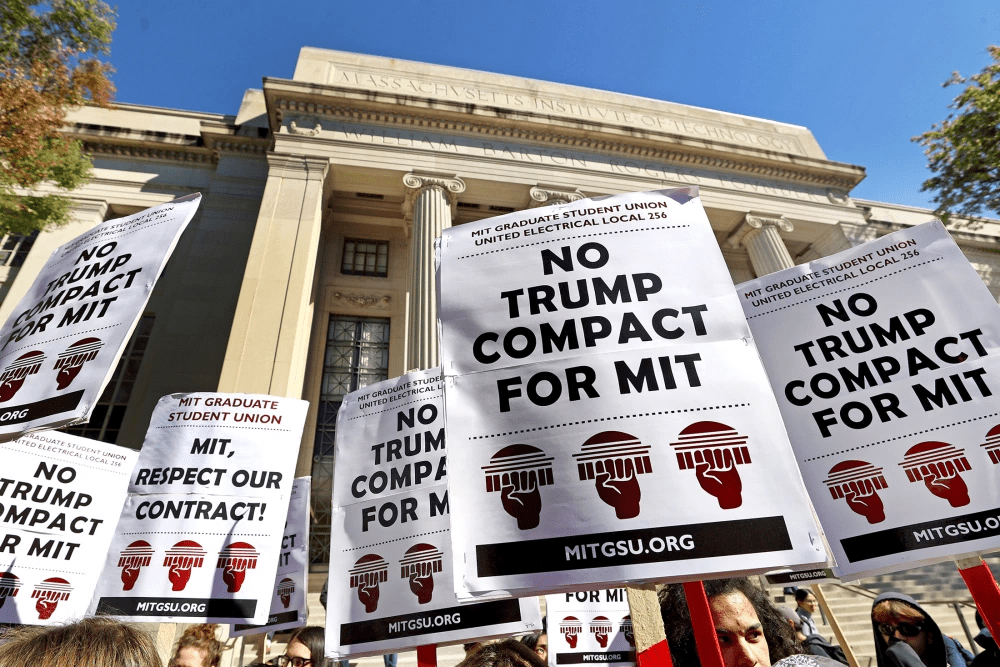

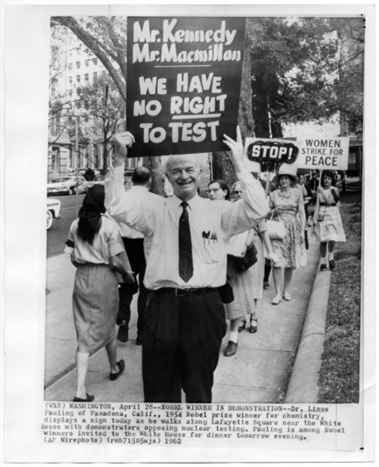

Activists campaign for a simple demand that seems to offer a solution to the near threat and the larger problem (e.g., “Ban the bomb”; “Stop nuclear testing,” “nuclear freeze”). Politicians and experts use public concern to institute some dimension of restraint, often negotiated arms control agreements, which manage public concerns. Testing of nuclear weapons has been a recurrent target for antinuclear campaigners, who have staged demonstrations in the streets of big cities and trespass at testing sites.

[Two time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling picketed the White House in 1963, the night before attending a dinner inside for Nobel prize winners (above).]

In this way, movements against nuclear weapons work, exercising influence even though activists don’t get anywhere near what they demand.

When the Cold War ended, the nuclear danger receded somewhat, and the number of nuclear weapons deployed by the big powers declined substantially. But restraint has been eroding and new nuclear threats have emerged. Arms control agreements have disappeared in a whole variety of ways:

We all know that the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s conduct of the Gaza War, both awful enough, could be much worse. Russia and Israel have their own nuclear weapons. America’s stalwart support of Israel and erratic alliance with Ukraine have encouraged other nations to try to develop their own nuclear weapons. Ulp.

Long before Trump first took the oath of office, the United States began developing ambitious and expensive plans to modernize its nuclear arsenal. And activists have been trying–with very little success–to reinvigorate public concern. It’s quite likely that a President Bush or Obama or Biden would have ordered some new nuclear testing. It’s extremely unlikely that any of them would have announced it in a fit of pique about China’s expansion of its nuclear forces.

So, Trump has done peace campaigners the favor of drawing public attention to nuclear weapons and signaling that he is not the president most of us would trust to make good decisions about the fate of the earth. The question now is whether people will pay attention and try to do something about it.