ICE is retreating from Minneapolis, but this time it’s not because of climate change. Instead, it’s a victory–albeit a very costly one–for the resistance to the Trump Administration and its migration policies.

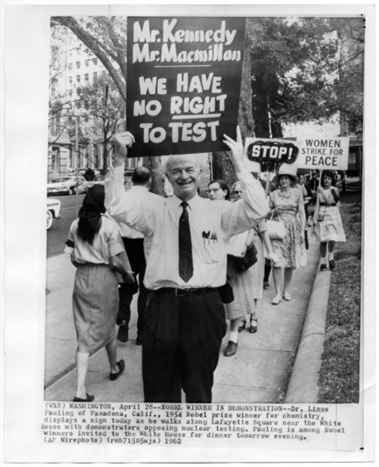

Like virtually all social movement victories, this one is partial, one that leaves a lot of work to be done. But it’s important to recognize the influence that protest campaigns sometimes exercise–as well as the costs and limits.

Tom Homan, just recently tasked with managing the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “surge” in Minneapolis, didn’t credit (or blame) resistance protesters with affecting his decision to end the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “surge” in Minneapolis, but their influence is unmistakable. Thousands of ICE agents will be leaving Minnesota as the Trump Administration looks to rework its prescence.

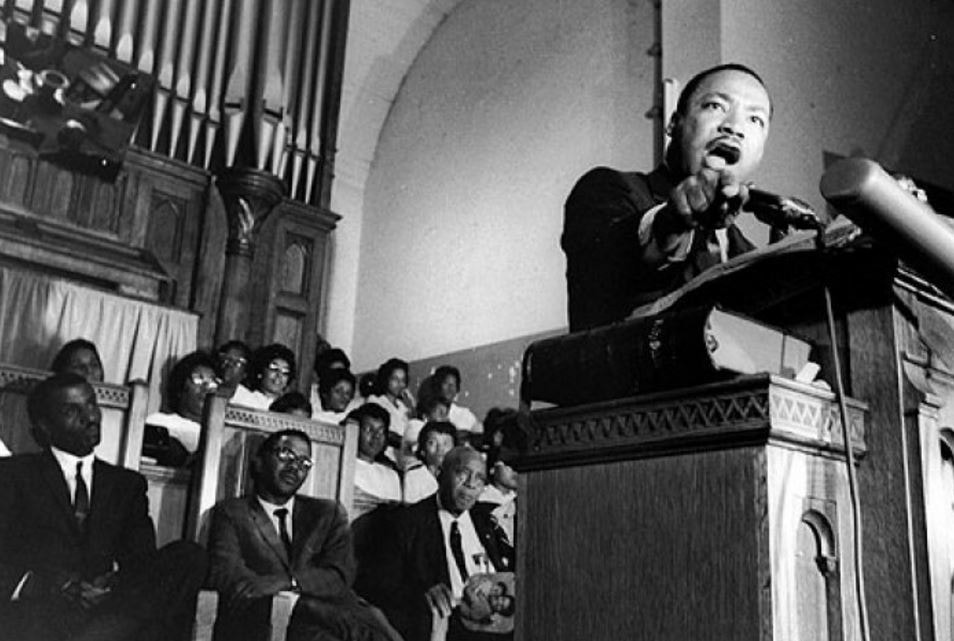

Of course, authorities virtually never credit protesters with influencing their best judgment or policies. Activists have to claim the credit that their opponents will always deny them. Without the protesters, things could have been even worse.

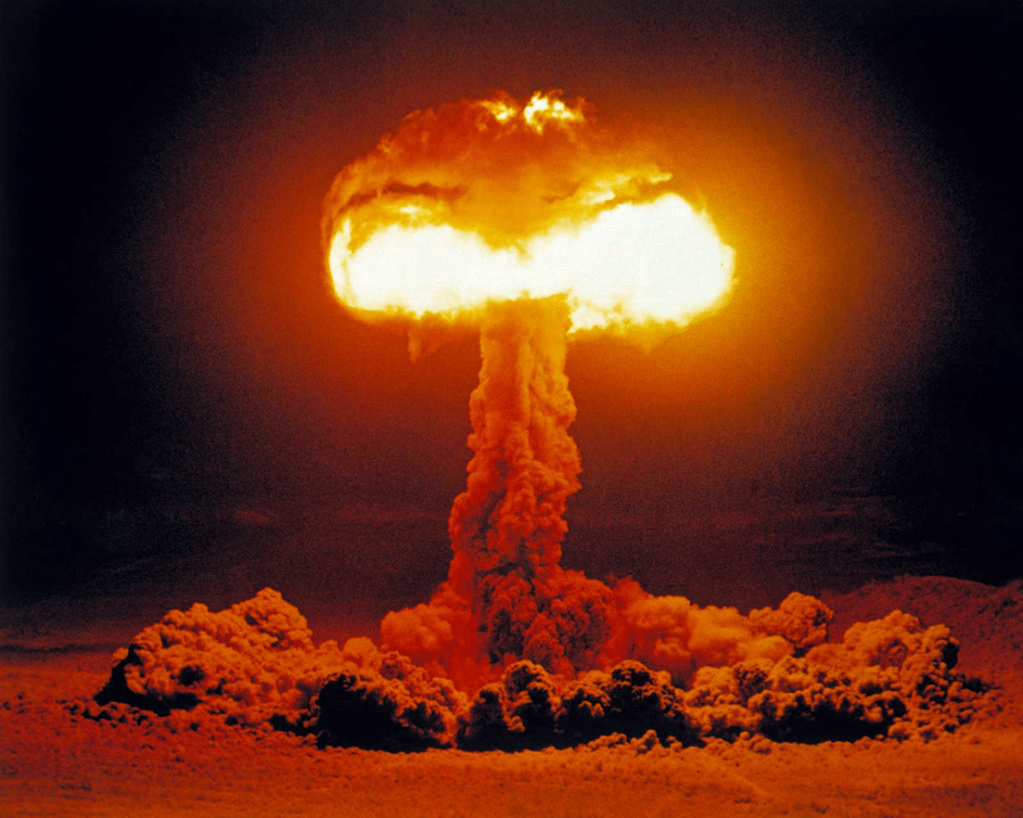

You’ll recall that the enforcement surge, featuring bands of masked federal workers roaming the streets to find people who looked foreign, was an effort to demonstrate Trump’s power in the streets. Facing overwhelming and disruptive resistance in larger cities, like Los Angeles and Chicago, the Trump Administration picked a smaller and whiter locale where ICE forces would far outnumber the local police force.

It didn’t work out so well.

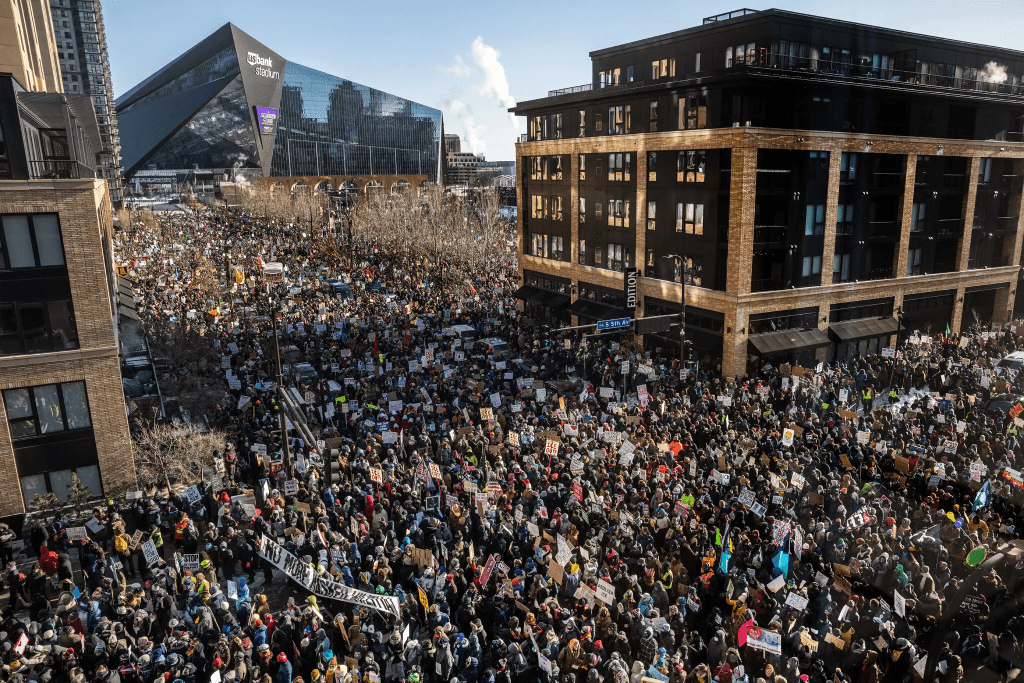

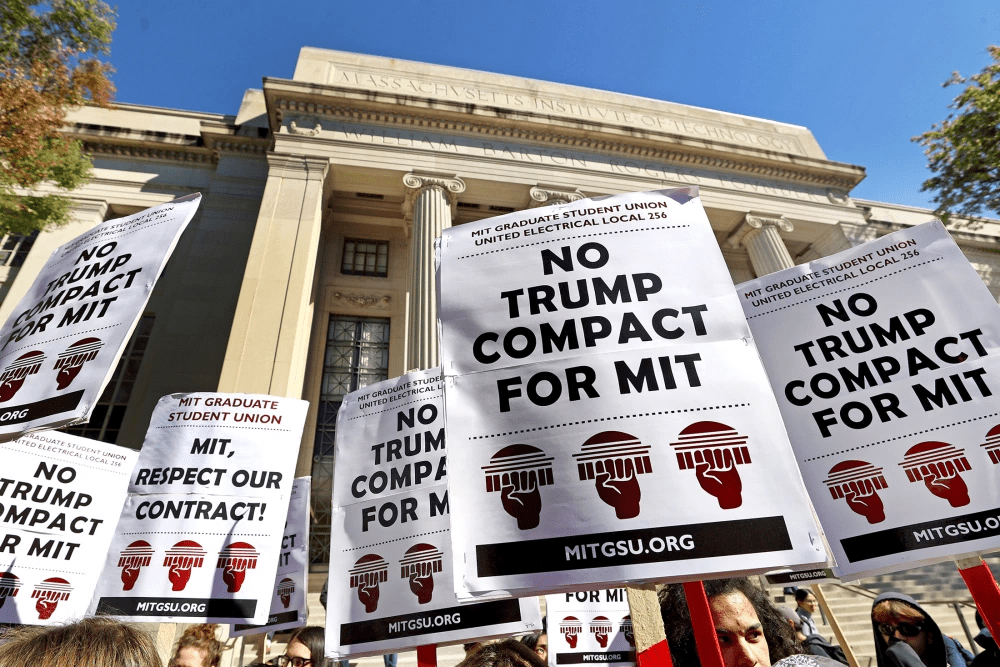

Minnesotans turned out in the cold to protest, vigorously and visibly; they had the right spirit and the right clothes. Building on dense civic networks, they set up ICE patrols to keep tabs on where the beefy men in tactical vests were going. And they ran small errands (groceries, kid transport) for neighbors who felt unsafe going outdoors. (See Margaret Killjoy’s substack for details. Thanks to Pam Oliver for the reference.) They drew attention from local and national media to the city and to ICE conduct, making for publicity and pressure.

ICE forces didn’t handle the spotlight very well. To be sure, it’s harder to do a job when strangers are watching (I’m alone now as I type), recording, and maybe even chanting or cursing. But law enforcement officers are supposed to be trained to deescalate. This means that the hard work of policing includes focusing on self-control and discipline even when protesters may hold up their phones and say nasty things. ICE overreacted to modest provocation, and agents recklessly shot and killed Renee Good, and then, a couple of weeks later, Alex Pretti. Administration officials dissembled and denied the facts of each murder, but local activists and media had captured the details on cell phone videos.

When Trump loyalists grew weak-kneed at the Administration’s explanations and justifications, the White House moved to deal with the immediate public relations problem. This meant quieting, at least for a while, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and disappearing Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino. Homan, presenting as the embodiment of the tough cop, was a clear step toward moderation.

Bolstered by the public reaction, institutional politicians issued demands: body cameras and identifying badges on ICE agents, rather than masks; changes in training and the rules of engagements; and just less. At this writing, funding for DHS remains in dispute in Congress, which means ongoing attention to provocative and unpopular policies. Democratic legislators and candidates for office are taking advantage of the moment.

Without the demonstrations and protests and without the local support for neighbors, we wouldn’t see ICE at work, and the Administration wouldn’t have had the public relations crisis to manage. Democratic spines would not be so strong, and public attention would wander…even more. This is what a protest win looks like.

But remember that this victory is partial and provisional. The Trump Administration, including Homan, has reaffirmed a commitment to mass deportations, and is constantly looking for more ways to flex power and back down opposition. For the moment, Caracas is a more congenial setting for the Administration than Minneapolis, but only as long as Americans continue to defend their rights and those of their neighbors.